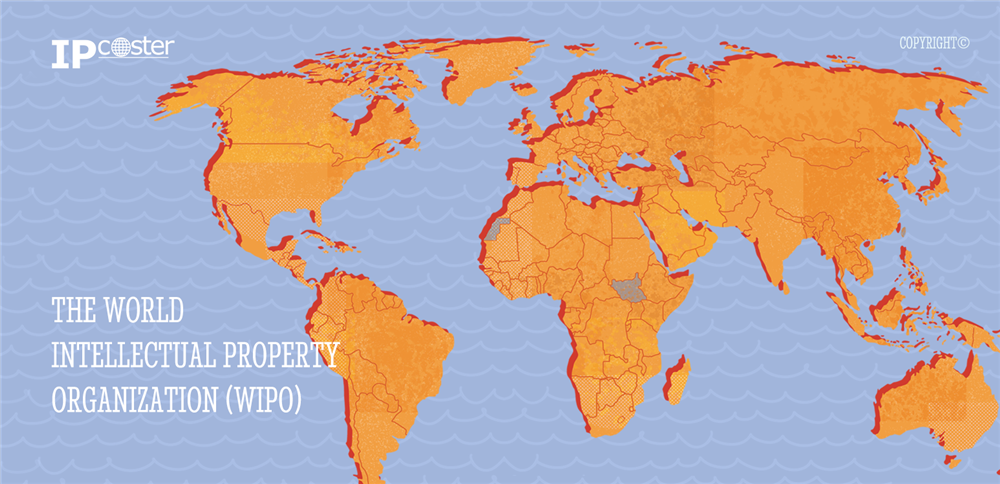

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is an international intellectual property (IP) specialist agency of the United Nations (UN) facilitating the protection and maintenance of IP rights across the globe. The WIPO acts as a global forum for IP services, as well as for international policy, information and cooperation.

The WIPO was established in 1967, and in its 58 years of operation, the number of member states has grown to a total of 194 countries. These member states have the collective right to contribute to the determination of the direction, budgeting and activities undertaken by the WIPO via the decision-making bodies of the Organization.

In order to become a member state of the WIPO, a state must be either: a member of the Paris Union for the Protection of Industrial Property or Berne Union for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works; a member of the UN or of any Specialized Agencies of the UN, or a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency, or party to the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

The WIPO provides a multitude of services and benefits for member states and IP worldwide, including a policy forum that aims to forge balanced IP rules across the world, services for the protection of IP and dispute resolution, as well as infrastructure to connect international IP systems and cooperation programs to foster a connected and cohesive global system.

In order to facilitate a solid worldwide IP system, the WIPO administers a variety of international treaties in relation to patents, trademarks, industrial designs and copyrights aiming to create a harmonization of IP laws and procedures across the globe. In the WIPO 's capacity as a specialized agency of the UN, it possesses an ongoing commitment to facilitate work with least developed and developing countries in order to assist them with an increased benefit of the worldwide IP system and encourage further participation in the global patent economy.

The WIPO not only facilitates cooperation between IP offices internationally, but assists in providing technical assistance and capacity-building programs which, in turn, helps countries to enhance their IP systems by providing training workshops, seminars, and support for developing IP infrastructure.

One of the most important elements of the work that is undertaken by the WIPO is the international registration systems that it facilitates. The WIPO administers the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), the Madrid System in relation to trademarks, and the Hague System for industrial designs.

Each of these systems simplifies and streamlines the process of obtaining and maintaining the protection of IP rights worldwide. In-depth information on each of these international systems can be found on our IP Academy page, however, each of these systems typically allows applicants to file one application to the WIPO which will then be sent to each designated member state for registration, according to which jurisdictions the applicant has stated that IP protection will be sought.

The WIPO also conducts vital research, analysis, and policy development in relation to the field of IP. This work aims to address emerging IP issues and challenges, such as those related to digital technologies, artificial intelligence and genetic resources, to name a few. The international office is also unique in that it addresses cross-border intellectual property issues and facilitates the harmonization of IP systems and practices among different countries.

Overall, the WIPO plays a crucial role in promoting the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights worldwide, fostering innovation, creativity, and economic development.

Are you interested in filing for IP rights with the WIPO? Contact us here!

(1) (1).png)

The African Intellectual Property Organization, officially the Organisation Africaine de la Propriété Intellectuelle (OAPI), is a regional intellectual property organization and office comprising 17 member states across the African region.

Established on September 13, 1962, the OAPI is headquartered in Yaoundé, Cameroon, and encompasses the member states of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Comoros, the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, Chad and Togo. It operates under the revised Bangui Agreement of 1999 and 2015 with the primary objective of facilitating a unified and streamlined system for the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights across its member states. In doing so, the Office helps to foster innovation, creativity, and economic development across the region. Moreover, the centralization of IP administration by the OAPI ensures that applicants and rights holders can secure and manage their IP efficiently and uniformly across member states.

The OAPI offers a wide range of services to facilitate the registration and protection of various forms of intellectual property, including patents, trademarks, industrial designs, and geographical indications, among others. By providing a single application process that grants IP protection in all member states, the OAPI significantly reduces the administrative load and costs associated with obtaining IP rights in multiple jurisdictions individually.

This system not only simplifies the process for applicants but also ensures a consistent application of IP laws and standards across the region, promoting legal certainty and stability for businesses and individual inventors. Owing to the fact that all OAPI member states are governed by the common law set forth by the Bangui Agreement, it is not possible to designate certain member states for IP protection. Consequently, an OAPI registered right will be valid in all member states simultaneously.

In addition to facilitating a system for regional IP rights, the OAPI also allows for several initiatives and international collaborations with the aim of raising awareness and providing education to all stakeholders alike regarding the importance of intellectual property. As such, the organization conducts and hosts several training programs, workshops, and seminars aimed at enhancing the skill set and capacity of IP professionals, officials, applicants and the general public. These initiatives are an important element in the maintenance of a robust IP system in the African region, helping to cultivate a stable basis for the protection of innovation and subsequent economic upturn.

The OAPI also collaborates with multiple international organizations, including the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), in order to align its interests and actions with global best practices and legal framework. Additionally, the OAPI is a party to both the Hague Agreement and the Madrid Protocol, allowing for the international registration of various IP types within the regional organization. Such collaborations can prove vital in forging an effective IP system for the region, also encouraging applicants from across the world to file for IP protection in OAPI member states.

The OAPI plays a pivotal role in supporting economic development by encouraging foreign investment and global IP applications. By providing a reliable system for the protection of an applicant's IP portfolio, the OAPI assists in facilitating an attractive environment for investors who seek to capitalize on the region's growth potential. This is due to the fact that secure and enforceable IP rights are essential for companies looking to establish operations in Africa, protecting their innovations and brand identity from infringement. Furthermore, the promotion of IP rights in the region also helps to provide for the commercialization of local innovations and the development of new industries, contributing to further economic growth and an increase in employment opportunities.

Overall, the OAPI is instrumental in advancing intellectual property protection across the African region, fostering innovation across its 17 member states through a centralized IP system, harmonized IP laws, and the facilitation of training in regards to the IP field. In providing a cohesive system for the protection of IP rights, the OAPI also acts as a catalyst for economic development in the region.

Common Questions

If I want coverage in Francophone Africa, should I file via OAPI or file nationally country-by-country?

If your target markets are largely within OAPI's 17 member states, OAPI's centralized system can be an efficient route because one procedure can cover the region. If your plan includes non-OAPI African states, you may need a mixed strategy (OAPI + national and/or another regional route).

What's the biggest operational "trap" with OAPI filings?

Assuming that all African countries are included in one organization. In reality, OAPI is one regional system for specific member states; other African countries sit outside it and require different filing routes.

Do I need a local representative for OAPI?

Yes, a registered patent attorney is required for foreign applicants.

How can IP-Coster help with OAPI work end-to-end?

If you’re planning protection across OAPI member states, IP-Coster can support the workflow from initial budget estimation to coordinating filings and ongoing maintenance across your selected jurisdictions, so you can manage the process in one place rather than stitching together separate tools and providers.

.png)

Managing the lifecycle of a patent, from the initial filing of a PCT application to maintaining its validity for 20 years or more, can be complex and resource-intensive. IP-Coster simplifies this process, offering a centralized platform to handle every stage of patent prosecution and protection efficiently. With our support, clients can focus on innovation while we manage the details.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) enables applicants to file a single patent application, which can then enter national or regional phases to seek protection in up to 158 countries and regions. However, the PCT does not provides a single “international patent”. Instead, it streamlines the process of obtaining separate national or regional patents.

Filing traditional PCT application involves several steps: preparing documents, obtaining necessary signatures, and submitting physical copies to a receiving office. This process can be time-consuming, especially when coordinating with legal representatives and handling extensive paperwork.

Simplifying PCT Filing with IP-Coster

IP-Coster’s platform eliminates these hurdles by offering a centralized, user-friendly solution. Our experienced attorneys handle the entire PCT application process online, ensuring timely submission to any of the 89 available receiving offices. We manage all communication digitally, eliminating the need for physical paperwork and reducing administrative overhead.

Entering National or Regional Phases

Under the PCT agreement, applicants must transition their applications into the national or regional phases to seek patent protection in specific jurisdictions. This step typically occurs within 30 or 31 months from the earliest priority date, depending on the regulations of each country or region.

Navigating this phase requires tailored strategies for each jurisdiction. At IP-Coster, our team helps clients select the best options for their needs, ensuring a smooth transition and increasing the likelihood of successful patent grants.

Managing Independent Prosecution in Each Jurisdiction

During national or regional phases, patent prosecution proceeds independently in each chosen jurisdiction. IP-Coster partners with a global network of trusted agents to provide professional and reliable representation for our clients, ensuring compliance with local legal and procedural requirements.

Our platform allows clients to manage their intellectual property seamlessly across multiple jurisdictions, all within the same intuitive interface they used to begin their patent journey. From filing to grant, IP-Coster supports clients every step of the way.

Maintaining Patent Validity

Once patents are granted, maintaining their validity requires the timely payment of annuities in each jurisdiction. This ongoing obligation is essential to ensure that the rights conferred by the patent remain secure.

Through IP-Coster, clients can manage annuity payments efficiently, reducing administrative complexity and minimizing the risk of missed deadlines. This ensures patents remain secure while clients focus on leveraging their intellectual property.

Extending Patent Terms

In certain industries, such as pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, patents may be eligible for term extensions to compensate for time lost during regulatory approval processes. These extensions can add up to five years to the standard 20-year patent term, depending on specific criteria and jurisdictional regulations. Each case requires a thorough assessment to determine eligibility for such extensions.

At IP-Coster, our experienced professionals are ready to evaluate your unique situation and guide you through the process of securing potential patent term extensions, ensuring that your intellectual property enjoys the maximum protection available.

Losing your patent priority rights can feel like a serious setback but in many cases, you may be able to restore them. Depending on the country and circumstances, two main legal grounds can support reinstatement:

You acted with due care, or the delay was unintentional.

Let’s take a closer look at how each option works.

What Are Patent Priority Rights?

When you file a patent application, you typically have 12 months to file related applications elsewhere while keeping your original filing date. This is called your “priority right”.

If you miss this deadline, your right to claim priority may lapse — but many countries that follow international agreements like the Paris Convention or the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) offer a way to restore it. For example, under the PCT, you have up to 2 months after the missed deadline to request restoration as long as you meet either the due care or unintentionality standard.

Option 1: Restoration Based on Due Care

This is the more demanding option. You must show that you did everything a reasonable and careful applicant would have done and still missed the deadline despite your efforts. Examples of valid reasons may include:

Illness or absence of you or your agent

System failures or technical problems

Miscommunication with your agent

Mistakes by staff or clerical errors

Postal service delays or force majeure events (e.g. natural disasters)

You’ll need to provide a detailed explanation of what happened, along with any supporting evidence. The patent office will review your actions up until the deadline to determine whether you truly exercised due care.

Option 2: Restoration Based on Unintentional Delay

This standard is less strict. To qualify, you must show that the missed deadline was not intentional — that is, you meant to file on time, but something went wrong. Common situations that may qualify:

You misunderstood the filing requirements or laws

You were unaware of the deadline

You relied on incorrect information or advice

Here, the focus is on your intent, rather than whether your actions met a high diligence standard.

Submitting a Statement of Reasons

Whether applying under due care or unintentionality, you’ll need to file a Statement of Reasons explaining:

Why you missed the priority deadline

Which criterion you’re relying on (due care or unintentional)

Any supporting documents (e.g. emails, system logs, medical records)

The receiving patent office will review your statement and may request more information if needed. A strong, well-documented explanation improves your chances of success.

Summary

While losing a priority right can feel like a major obstacle, you may still have options to recover it, especially if the delay was unintentional or you acted with reasonable care. However, restoration is time-sensitive, so act quickly. If you’re unsure which route to take or how to prepare your application, professional guidance can be of great assistance.

Need help? Contact us through our website: www.ip-coster.com

Common Questions

Is reinstatement available everywhere, or only in some countries?

Reinstatement is not available everywhere. Availability depends on the jurisdiction and whether it accepts restoration under the Paris Convention/PCT framework (and on what criteria).

Are there extra official fees for restoration, and should I budget attorney time too?

Many offices often charge an official restoration fee, and you should also budget for attorney time to draft the statement, collect evidence, and manage tight deadlines.

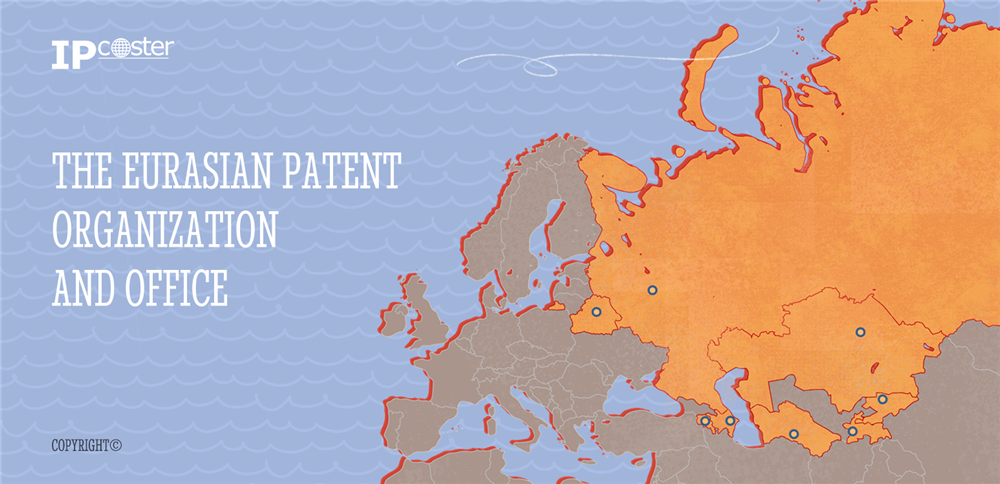

The Eurasian Patent Organization and Office, known as EAPO, is an intergovernmental organization established in 1995. Its main goal is to support the development and protection of intellectual property across the region, based on the Eurasian Patent Convention. This convention was first signed on September 9, 1994, and officially came into force on August 12, 1995, which formally created the EAPO.

The organization includes member states from both the Commonwealth of Independent States and some countries outside of it, promoting cooperation in intellectual property matters. As of 2025, the member states are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. The EAPO is headquartered in Russia, and Russian is its official language.

The EAPO’s primary role is to provide intellectual property protection for inventions and industrial designs through a single Eurasian application that is valid in all eight member states. This system simplifies the application process, allowing inventors and businesses to protect their ideas in multiple countries with one procedure. It reduces costs, saves time, and increases efficiency, which helps drive innovation and technology growth in the region.

Since its establishment, the EAPO has granted Eurasian patents. In June 2021, it also started accepting applications for regional industrial design protection after adopting a new protocol in 2019.

To get a Eurasian patent valid in all member states, an applicant needs to file just one application with the EAPO. This application can be submitted in any language but must be followed by a Russian translation within two months, or within four months if the applicant pays an extra fee. A Eurasian patent can also be obtained based on a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application by entering the Eurasian regional phase within 31 months from the earliest priority date.

All Eurasian patent applications go through a thorough examination. For regular applications, the applicant must request this examination within six months after the publication of the search report. For PCT-based applications, the request must be made when entering the regional phase.

After a Eurasian patent is granted, the patent owner can choose in which member states they want to maintain the patent. They can also restore patents that lapsed due to unpaid fees. In some cases, the owner may extend the validity of the patent for specific types of inventions. Between the time the patent is published and the payment of the first annual fee, the patent owner holds exclusive rights to their invention across all member states.

All fees related to Eurasian patents or industrial designs are paid directly to the EAPO, not to each member state separately. The filing fee may be reduced by 25 percent if the application includes an international or PCT search report from another authorized office. The fee can be reduced by 40 percent if the report was produced by the Eurasian Patent Office.

Since 2022, the EAPO has also served as an international search authority and an international preliminary examination authority under the PCT system.

The EAPO is active in international cooperation. It has signed agreements with organizations such as the African Intellectual Property Organization, the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization, the European Union Intellectual Property Office, the European Patent Office, and the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Additionally, the EAPO participates in Patent Prosecution Highway programs with several intellectual property offices worldwide. These include the Chinese Patent Office, the Korean Intellectual Property Office, and the Finnish Patent and Registration Office. These programs help speed up the patent examination process by sharing examination results between offices.

The EAPO’s dedication to intellectual property rights highlights its important role in supporting research, innovation, and economic growth in the region. If you want to learn more about how to apply for intellectual property protection in Eurasia or through the EAPO, please contact us via our social media channels or here!

Common Questions

Do I need a local representative for EAPO?

Yes, a registered Eurasian patent attorney is required for foreign applicants.

When is EAPO not the best choice, even if I want protection in the region?

If you only need protection in one member country, or your key market is outside the EAPO member states, a national filing (or a different regional route) can be more targeted. The practical step is to map your actual sales/manufacturing countries first, then choose the route.

I'm considering EAPO, but I need a clear budget first. What's the fastest way to get one?

Start with an initial quotation that separates official fees from professional fees, so you can see what is fixed vs what depends on attorney work. On IP-Coster, you can begin with a structured estimate and a transparent breakdown before choosing the route.

Intellectual property is a pinnacle of modern society, with a multitude of popular cultures being governed by undercurrents of IP without many realising. From chart music to toy brands and beyond, there is much to explore when it comes to some of the most well-known and non-traditional intellectual property, and we have explored some of the finest examples.

Trademarks are one of the most valuable types of IP used by some of the biggest powerhouses in all industries, and whilst many marks are more traditional, some businesses have chosen to go down a more atypical route, resulting in some of the most well-known and recognisable IP.

These include the toy company Hasbro, which took a chance on, and successfully registered, the iconic and widely recognised Play-Doh scent on May 15, 2018 with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Whilst not unheard of, scent marks are among one of the lesser obtained trademark types, due to the more stringent requirements which need to be met in order to obtain scent mark protection. In the US for example, it is outlined that the "amount of evidence required to establish that a scent or fragrance functions as a mark is substantial".

Such evidence is required to demonstrate that the scent itself has acquired distinctiveness. Further, the scent of the item should not be an important practical function, rather, it should merely assist as an identifying element used to distinguish the brand to which it relates.

Play-Doh managed to achieve this feat, with the scent described on the trademark register as a "sweet, slightly musky, vanilla fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, combined with the smell of a salted, wheat-based dough." Although a vast majority may not pick up on the particulars of the fragrance by simply smelling it, the nostalgic scent is distinctive enough on the whole to be recognisable to many as the smell which belongs to Play-Doh. The scent has also been released as a perfume, which would no doubt be a niche and memorable gift to anyone with fond memories of using Play-Doh.

Unlike trademark protection, copyright can prove more nuanced when it comes to lesser traditional forms of creative work. Commonly, people would consider paintings or literary works as typical copyright works, but tattoo artist S. Victor Whitmill made headlines with regards to his iconic tattoo design made especially for the boxing legend Mike Tyson. The tattoo, which was initially created in 2003 by Mr. Whitmill, created a stir when seen in the hit film "The Hangover II". The film depicted a character played by Ed Helms sporting the tattoo on his face, duplicating the design created for Tyson.

A mere few weeks prior to the release of the film, which ended up becoming the highest grossing comedy film to date, Whitmill instigated copyright infringement proceedings against Warner Brothers over the use of the tattoo design. Whilst the initially sought after preliminary injunction was denied, the Judge noted there was merit to the case and the lawsuit ensued. The case was settled with the terms kept under lock and key, however, Warner Brothers acknowledged a few weeks before a conclusion was reached that they may have considered digitally altering the tattoo so as to eliminate potential infringement.

The unusual case not only sheds light on the complexities of intellectual property protection in a fast evolving digital landscape, but on the intricacies of copyright as a whole. Whilst other works such as art pieces or literary novels have a plethora of legal precedent surrounding their protection, tattoos are more unique in terms of copyright protection.

Copyright law in the UK allows the designer of the tattoo to enjoy the IP rights to the piece, entitling them to any royalties should an image of the tattoo be reproduced. This means that even though the tattoo may be unique to you, but a tattoo artist designed it, the copyright will lay with the artist. On the other hand, if a person creates a tattoo design themselves, the copyright will belong to them. These lines of copyright ownership can become blurred in cases where an artist is commissioned, for example, to create a custom design using your ideas, at which point joint ownership may be considered.

Whilst protecting more obscure or unusual intellectual property possesses its risks and requires much thought, trademarks such as Play-Doh and copyright battles such as Whitmill's tattoo design demonstrate that risks can pave the way to great reward when it comes to IP. If you would like advice on the protection of your intellectual property, please contact us.